Artistic methods often exist somewhere in between those two approaches. On the other hand, the methods presented for PCG in video games represent a more goal-oriented approach, with the algorithm being led by the designer's or player's ideas.

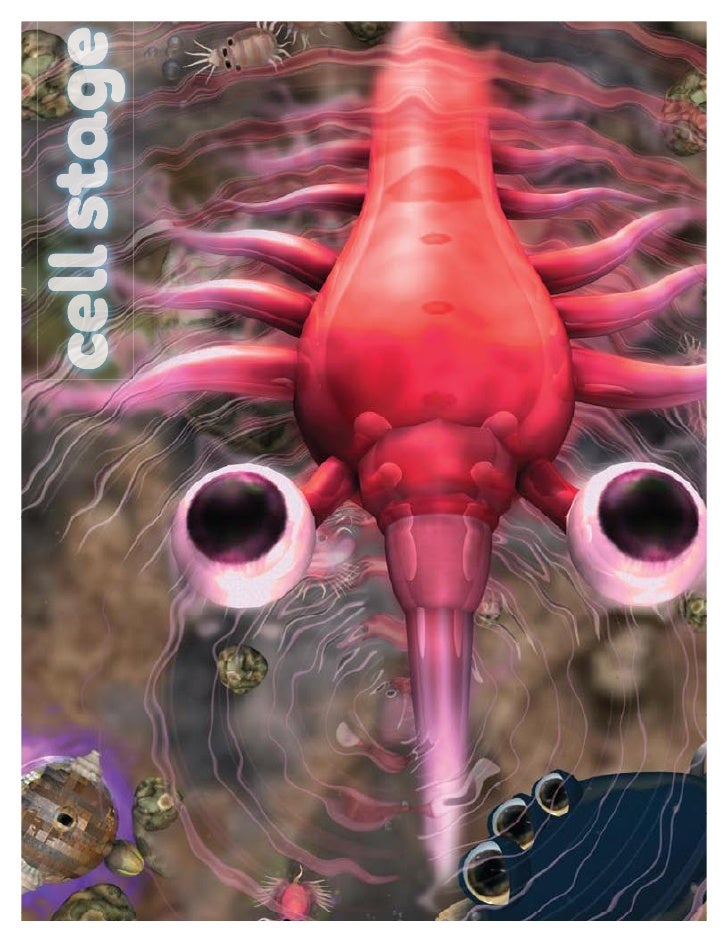

ALife methods present a process-oriented, computing centric field. As we have researched in preparation for this survey, Artificial life (ALife), the arts (Art) and video games (Games) have emerged as the major fields in which methods for generating the morphology of virtual creatures are developed and used. Therefore, we have sought to separate the works based on the primary methods and have divided this paper into sections on L-systems, cellular automata, gene regulatory networks, and so forth. Instead, we aimed to learn under which circumstances each method is useful and how it relates to others. Simply organising this review chronologically and listing work after work tells us little of each method's purpose and the context under which it was developed. Making “heads or tails” of such a huge area has been difficult. L-systems, rigid bodies, finite elements, gene regulatory networks and more. Virtual creatures represent a field with far-ranging applications, from robotics, arts and video games over sorting algorithms to the simulation of ecosystems for learning about evolutionary issues such as what comes first behaviour or morphology? Similarly, the methods for generating artificial life forms are plentiful cellular automata. and the annual virtual creatures competition bear witness to. This paper will describe many such methods in detail.Ĭomputer-generated creatures are not only interesting subjects of study in their own right, They can teach animators and creature designers how to become better at their craft, and represent a fun and intriguing way to learn about evolution, as the anecdotes of Lehman et al. This approach started with the works of Karl Sims and has remained popular to this day. Instead, the machine can learn about anatomy through physical simulation and evolving forms.

However, except for the works of Toor & Bertsch described later in this paper, which isn't an approach that has gained momentum when it comes to modelling creature morphology. While a human artist studies anatomy and existing works to get better at their job, what will the computer study to get better at understanding creature morphology? Increasingly with the rising popularity of machine learning, in other fields, the answer has been that the computer studies what the human studies. When artists design and model creatures, they are often inspired by real-life animals and anatomy. This review is uniting a number of fields that would typically be disparate ALife, games and the arts. Research fields such as mixed-initiative co-creative interfaces are introducing computational agents as full creators and collaborators. As procedural content generation methods gain popularity, we now realise that not only humans can initiate creation. In this paper, we present a review of methods for the procedural generation of virtual creatures.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)